The trial of former LRA Commander Dominic Ongwen resumed on Tuesday, September 18, at the International Criminal Court in The Hague, with an opening statement from the defense. Miles and miles away, Ugandans gathered around televisions and hunched over radios, following each detail of the proceedings. Many attended screening events organized by the ICC itself. The court endeavored to make the trial accessible to those people whose lives were torn apart by conflict. The Justice and Reconciliation Project hosted one such screening in the organization offices at Koro-Pida.

Some one hundred participants arrived by bus from various locations. They crammed together on white, plastic chairs. Mothers brought small children, who sat in their laps or played on the floor. The screening was near silent. Attendees only spoke during the breaks, when they shared snacks and soda, or relaxed in a courtyard.

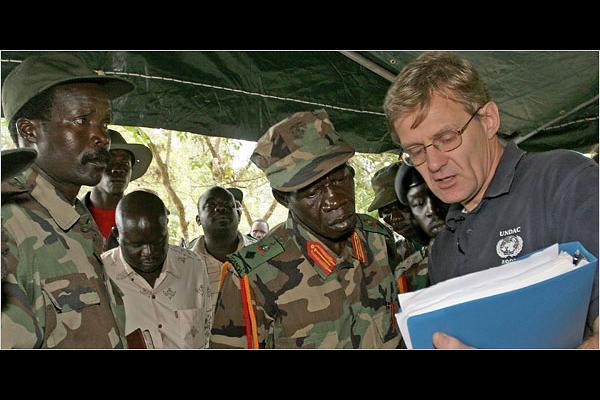

The ICC strove to create an open space, where the community could truly engage with the trial, however distant. Eric MP Odong, a field assistant, said, “We are here to execute the mandate of the registry of the court, and to serve the victim community.”

The screening at JRP was not the first of its kind nor was it the only event in the area. Another screening, this one at Gulu District Hall, was so packed that people spilled on to the ground outside. Engagement in the case is high. “We are responding to the interest and the demand of communities, who want to follow the trial,” said Jimmy Otim, another field assistant. In fact, the ICC has organized screening events since Ongwen’s trial began two years ago. Court representatives travel to areas with little electricity and bad roads in order to disseminate information.

Many of these locations were the sight of LRA attacks. Emotions run high and memories of war are fresh. “My better half of my life is the conflict,” said Otim. “That is why I studied conflict, to understand why people suffer.” His work is personal. Otim also vividly remembers trial screenings at which community members corroborated the information on screen, pointing to places where violence occurred. As a result, counselors and facilitators are always present.

Responses to these screenings have been overwhelmingly positive. According to Otim, “[The community] is happy that what happened to them is being heard in an independent court, they are happy that what happened to them is being recognized. They are happy that maybe, ultimately, they’ll get justice.”

Odong agrees. “I see justice being done,” he said. “The prosecution did its part and now it is the defense’s turn. I see justice by allowing different parties to express themselves.” Odong claims he will be satisfied regardless of the outcome. “The process of the trial will have cleansed the accused, even if he is set free,” he said.

The trial culminates a longer hunt for Ongwen and his fellow rebels. More than eleven years ago, the ICC issued a warrant for his arrest, along with warrants for Vincent Otti and enigmatic leader Joseph Kony. In 2014, Ongwen was captured along the border between South Sudan and the Central African Republic, and turned over to the court. His is a painful saga, and one that contains the complex history of the conflict itself.

Ongwen was abducted by the LRA when he was nine years old. He was walking to primary school near Gulu. Like many other young boys, he was forced to watch and later commit heinous acts, and was brutally inducted into the army. Unlike many, however, Ongwen ascended the ranks. He reached the LRA control alter and came to command the notorious Sinia Brigade. This wing of the LRA attacked internally displaced person’s camps, specifically Abok, Odek, Lukodi and Pajule. Ongwen himself is charged with 70 counts of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including abducting children to use as soldiers and sex slaves.

Thus, Ongwen can be cast as both victim and perpetrator; a man whose life was altered by the conflict, and a man who altered the lives of others. He is also the first and lowest ranking member of the LRA to be tried internationally. Kony is still at large. Otti is presumed dead.

Seeing such a man stand trial can be divisive and upsetting. Some want him in jail, punished for years of havoc, while others believe he was boy brainwashed, and so deserves amnesty. Many community members are former abductees themselves, and do not understand why they have been forgiven and Ongwen has not.

Andrew Simbo has worked in transitional justice in both Uganda and Sierra Leone. He is currently the executive director of Uganda Women’s Action Program. The organization helps to bring more women and children to the ICC screenings. He claims that communities have now become fully reintegrated, “Those who actually carried out the atrocities are in the communities now. They have been given amnesty. They are the boda boda riders; some are musicians. They are there. They have been integrated into the community,” He added, passionately, “people have moved on.” While UWAP remains a neutral body, Simbo asserts it can be difficult to explain the mere fact of Ongwen’s charges to community members.

Justin Ocan, a community representative from Lukodi, believes that the screenings themselves will lead to a better future. “We tell these populations that this is also a learning environment, because we need to learn this time, so that you transfer the knowledge you gained from this screening to your children, so that in the future they don’t engage themselves in such kinds of practices,” he said.

Regardless of what the court decides, or even of divided opinions, one thing is certain. Sharing information, and making that information accessible, is crucial. It brings people together. It binds them in knowledge and informed conversation. It cements community. Justice itself is a long and twisting process, and its outcomes can never be universally satisfying. Yet, Ocan puts it beautifully, if simply: “Justice is a collective effort to attain a peaceful life.”

As the trial continues, people of many different opinions, can come together and watch it unfold.