“Ex-LRA abductees struggle to survive,” Daily Monitor, 7 April 2012

http://www.monitor.co.ug/SpecialReports/-/688342/1381202/-/item/0/-/nrtagaz/-/index.html

By Moses Akena

Eighteen years ago in an afternoon of May 1994, the then 10-year-old Evelyn Amony’s innocence and education was robbed off her after she was abducted by the Lord’s Resistance Army rebels from her way home after classes at Atiak Pupwonya Primary School in Atiak Sub-county, Amuru District.

Now 28, Amony, who was in Primary Four when she was abducted, was taken with three children below 12 years old as was preferred by the rebels. She says she was immediately taken to Kilak hills (Kony’s base then) where she baby sat most of his children, including two she identified as Salim and Ali.

However, her group later left for Palutaka in Sudan in October of that year where she stayed at the home of the LRA leader, whom she said guarded her jealously. “While in Uganda, he used to tell me that he will not let any man touch me vowing to get for me a good man at the right time to marry,” she reminiscences.

Ironically, one day in 1997, it did not occur to her that he (Kony) was the ‘good man’.

Amony, who at the time was 15 years old, says she vehemently resisted advances by Kony because he was her father’s age mate.

What astonished her, Amony recalls, is the rebel leader telling her that she should blame her mother for bearing her with her beauty and for her being hardworking and tidy.

“I tried escaping that night from the camp but I couldn’t go far because the place is mountainous and I didn’t know that I was rotating within the same place,” she says.

Tried to escape

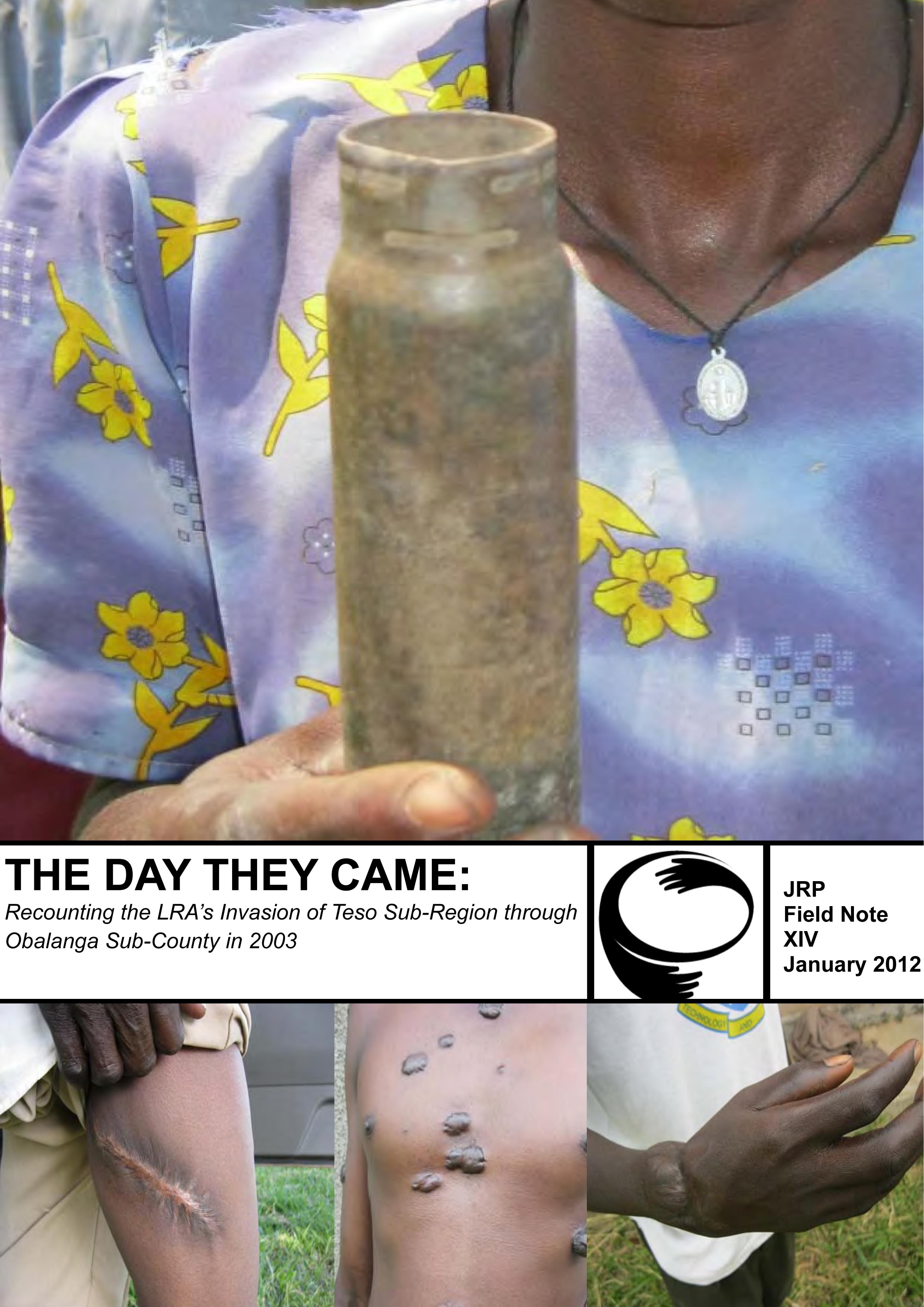

After spending the night in the bush, an LRA patrol team arrested her the next day and took her back to the camp. Here, she met and narrated her ordeal to the senior LRA commanders then; Otti Lagony and Vincent Otti. This could not stop the mandatory punishment of 50 strokes of the cane that such a case attracted.

“He (Kony) told them that he is the final man and immediately ordered me to go and prepare tea despite feeling pain on my buttocks from the beating,” she says. Amony later conceived and bore three children for Kony before her eventual escape in August 2005.

Now eight years after her return, Ms Amony bears no hallmark of the grandeur she anticipated.

Squeezed in a grass-thatched mud and wattle hut in Kirombe, a Gulu Municipality suburb, Amony, who has also married a former abductee, is struggling to take care of the three children and two others that she adopted.

“I have a challenge taking care of the three children because I don’t know their clan though I hear their father comes from Odek Sub-county,” the LRA victim adds.

Luckily, two of her eldest children (all girls) are being taken care of by their paternal uncle and are studying in a Kampala primary school .

Aryemo’s case

Amony’s dilemma is shared by 27-year-old Grace Aryemo, a mother of three, who shares a small grass- thatched hut with her three children in Laroo, three kilometres out of Gulu Town near Gulu University.

Rejected by her family in Lacekocot in Pader District and castigated together with her children by her aunt whom she was staying with for being an “evil person,” she found solace in crushing rocks at a stone quarry near her home.

Once in a while, she manages to crush a container of about 100kgs of which she gets about Shs2,000 a day. However, she says she has hardly got any money in the last one month, adding with a melancholic tone of how she and her children occasionally forgo food when there is no money.

For Amony, a trip back home to Atiak presents chilling memories because people in the area blame her group for the April 1995 incident in which more than 300 people were massacred by the LRA.

She says at worst, she only spends two days at home because it is only her father who is fond of her. She cannot dare ask her brothers for share of the family land.

Amony says the hostility extended to the children who are labeled ‘bush children’ might bring a similar problem in future.

Their concern is shared by hundreds of women, who at a tender age, were among more than 100,000 children abducted, coerced, and for the case of the girls, impregnated by senior LRA commanders.

Hundreds of children are believed to be in captivity of the LRA, most of them as child soldiers. The women, through their umbrella association, Women’s Advocacy Network, last week held a meeting in Gulu Town organised by several NGOs in the region.

They cited, in a memorandum read by Grace Acan, who was abducted from St. Mary’s College, Aboke, in 1996, denial of land and other property to them, stigma, and refusal to ask for forgiveness by their husbands, financial difficulty and favouritism of the male returnees as reasons for their concern.

They also say their family members and those of their husbands have rejected them and their children, accusing them of killing them while in the bush and carrying with them a curse.

Most of them after being rejected by their relatives and husbands have opted to rent houses near Gulu Town from where they have to live from hand to mouth.

Aryemo, for instance, makes beads at home which she sells to supplement what her husband, with whom she is yet to bear a child, gets from riding a boda boda motorcycle.

NGO’s work

Santo Okema, the programmes officer at Ker kwaro Acholi, a cultural organisation, responding to concerns raised by the women that they have been ignored by the cultural institution as has been the norm in the past, promised to raise their concerns at a meeting of traditional leaders.

Susan Blanch Alal, the programmes manager at World Vision Uganda Children of War Rehabilitation Programme, said more than 14,000 children have since benefited from their programme.

She added that the organisation came in to support former abductees and people affected by war after detecting challenges with their reintegration in the community.

“We have developed a proposal on how best to reintegrate the formerly abducted persons in the community and make their lives fruitful and peaceful with the other community members,” Alal says.

Mapenduzi Ojara, the district chairperson, says they are aware of the grievances of the women and promised to look for solutions through programmes like the Peace, Recovery and Development Plan for northern Uganda.

Big struggle

He says recovery from war is a complex process that calls for a lot of commitment from the government and development partners who he says should design projects that are relevant to the women.

“What we are looking for now is to empower the women to access services and to also offer them psychosocial support,” Ojara says. The women are also particularly upset that some of the men who returned from captivity are enjoying more limelight than the women and have not taken any steps to take care of their children or ask for forgiveness.

“It’s painful that they took us to the bush, abused us, and impregnated us. They know they were our abductors and they don’t want to come and ask us for forgiveness,” Aryemo narrates.

For instance, in January, former LRA spokesperson, 50-year-old Sam Kolo graduated from Gulu University with a degree in Business Administration and immediately set his ambitions on getting a Master degree.

For Amony and the other women, their beauty still remains but the good life they dreamt of in childhood has been robbed off them and it is a struggle to rekindle it, something that they may realise much later in life and with little significance.